- Home

- Brownlee, Victoria

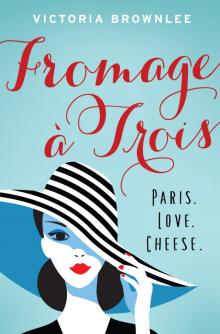

Fromage a Trois Page 4

Fromage a Trois Read online

Page 4

The hotel’s reception area occupied a former bakery and the view from the street looked like it had been lifted directly from a vintage black-and-white photo. The façade was decorated with murals of people in charming village settings and the word “Boulangerie” stood proudly in gold-and-black lettering above the window, vying for attention. Visible through the window was an array of perfect pink orchids and lush green ferns that brought the scene to life. The effect was like a little gateway to heaven, and it was to be my haven.

My room was only sixteen square meters but it was perfect. There was enough space for me, my luggage, and not much else really, but the best thing was that it was a big change from Paul’s apartment back home and it already felt a hundred times more wonderful. When I looked out the window at the rows of Haussmann-inspired buildings spanning the long, straight Rue de Poitou, something in my heart surged back to life.

I fell asleep to the sound of French cars driving by and sirens blaring in the distance. I slept blissfully for the next eight hours, waking only when my phone started buzzing.

“Hello, oui, bonjour,” I croaked, still not fully awake.

“It’s just me, love. It’s your mum. Are you OK?” She seemed thrown by me speaking French.

I stood up to try and get some blood running to my brain. “Mum, hi. How are things? God, I feel like I’ve been sleeping for days.”

“I’m fine. Are you OK? I’m still very worried about you, taking off quite suddenly like this. It’s very unsettling. And you leaving Paul, what a terrible shame. You two were perfect together.”

“Mum, stop. Paul didn’t give me much choice; we’ve been through this already. I’m fine. I’m in Paris. What could be wrong?”

“I don’t know, love. What are you going to do for money? Do you need any money?” She sounded worried but I was too exhausted to indulge her concerns.

“Eugh. Mum. No, I don’t need money. I’ll start looking for a job and an apartment soon. Everything is going to be fine. Better than fine. Everything is coming up roses,” I said, eyeing the jaunty floral wallpaper lining my room.

“OK, but promise me you’ll call when everything goes pear-shaped?”

“Fine,” I said, mostly to stop her from talking. “If anything goes wrong, I’ll let you know.”

I looked at the clock. It was already ten in the morning and the day was slipping by. “Mum, I’ve got to go,” I said hurriedly. “I’m heading out for coffee and then lunch. Love you.”

“You too, dear. Look after yourself.”

I hung up, feeling disgruntled. Where was the faith? I jumped in the shower and got ready to hit the Parisian boulevards.

Although I was only leaving Melbourne for a year, one of the hardest things about this whole plan had been saying good-bye to my friends. On my final night, Billie had hosted an overly boozy and emotional dinner for our group. We were all in tears by the end of the meal and to postpone saying good-bye, we ended up going for celebratory cocktails until the early hours. Not a great idea, when I was flying the next day.

I’d arrived at the airport more than a little frazzled. But Billie, the friend who always drinks water before bed and never looks hungover, thankfully saw me through check-in and pushed me through the international departure door with a hug and a smile.

Once I was through security, I’d ordered an overpriced glass of champagne to pass the time and take the edge off my hangover. I sat bleary-eyed, watching the planes flying in and out, nervous but so happy to be hitting the road again.

I was in my own world, already relishing my own company and feeling empowered. So much so that I missed my boarding call and panicked when I heard my name being announced grumpily over the loudspeaker. Shit, shit, shit! There is no way I am missing this plane, I’d thought frantically, as I’d sprinted to the gate.

But here in Paris, leaving the hotel, I felt like a completely different person. I felt refreshed after a long shower and I was in a much more receptive state to enjoy my newfound sense of freedom than I had been the night before, jet-lagged, slightly anxious, and still wrestling a fairly painful hangover.

I turned onto Rue de Poitou and basked in the picturesque beauty of my immediate surroundings. The morning sun was already heating up the streets. Having flown in directly from winter in Melbourne, it was a delight to be out in a summer dress and strappy shoes. Despite being in the heart of Paris—only a stone’s throw from Notre Dame where hordes of tourists would be snapping pictures and lining up to climb the towers in the hope of glimpsing Quasimodo—the Marais felt relatively quiet and peaceful. The buildings on either side of the road were home to envy-inducing apartments with vibrant planter boxes spilling over with flowers and foliage. Striking iron and glass street lamps amplified the feeling that I’d moved onto a movie set. My eyes devoured every unique detail. The straight lines of the almost-symmetrical apartment buildings were a sharp contrast to the hodgepodge of architecture that hugged the tram-ridden, wide streets of Melbourne.

Turning left, I found myself on Rue Vieille du Temple where a charming sign for an “École de Garçons” towered above a large green door. It was little things like this that had made me fall in love with Paris the first time around: snippets into a rich history that transported you into the past. The old boys school, which now looked like it had been converted into apartments, was only the width of one room and rose three stories high. It looked like something from a different era. I pictured the boys from the école walking up to the front doors and wondered if they had stopped to admire the beautiful street, or if for them, it was just life as usual. Perhaps after school they’d stop and pick up a chocolate croissant from the boulangerie next door.

Perhaps I should pick up a chocolate croissant from the boulangerie next door . . .

I nipped into the bakery and was immediately hit with the scent of flour and butter. The woman behind the counter handed me a still-warm pain au chocolat, the flaky pastry curling around the aromatic sticks of chocolate. “Heavenly,” I murmured to the empty paper bag, which was now scattered with pastry crumbs.

Reaching Rue de Bretagne, I spied a very sweet little table for one on the terrace of a café called Le Progrès—The Progress—which seemed fitting for my first stop of the day. I did a quick mental calculation of how long it’d been between coffees. I’d crossed so many time zones in the past few days that after a few excruciating minutes of mental calculation, I settled on “too long” and took the chair with a view of the street.

Not really knowing what to order, I asked for a café au lait. What arrived was a really weak version of a latte, with a strong hint of burnt coffee and the lingering flavor of long-life milk. It wasn’t particularly nice, but surrounded by Parisians at the cutest little French outdoor tables, it helped to bring my jet-lagged self back to life.

I was absolutely loving people-watching from my vantage point at the café, though I was still experiencing that wave of nausea that comes with swapping time zones and seasons. I thought back to the exasperatingly long flight that had brought me here and remembered the wave of relief that had flooded through me as soon as my feet had hit the airport corridor at Charles de Gaulle. “Sweet freedom,” I’d said softly to myself as people rushed past me into the border control queue.

It had felt like an age ago that I’d made that same journey into Paris, flying in solo with stars in my eyes. I’d arrived with a steely determination both times, though for different reasons, and as people buzzed about, kissing each other on both cheeks and picking up their chic baggage from the carousel, I’d flung a scarf over my shoulders and headed towards the taxi stand.

I’d have to figure out the metro today, though, I thought to myself. Last night all I could focus on was getting to the hotel, getting a decent night’s sleep, and downing a generously-sized glass of vin rouge. But now, looking at the café’s price list hanging helpfully in the window, I wondered just how expensive Paris had become and how economical I’d need to be. When

I was in Europe with Paul, I was still a student and everything felt expensive; but even now, as I sat and converted the prices for wine and coffee into Australian dollars, I began to feel a little nervous. I pulled out the rough Paris budget I’d done on the back of a sick bag on the plane. I’d calculated that with money for rent, food, wine, and the odd shopping splurge, I would run out of my life savings in eight weeks. Now it seemed like it’d be closer to six weeks.

What a grim prospect, I thought.

But then again, I was in Paris for the first time in years. And while I didn’t want to fritter away all of my money swanning about the Marais eating and shopping for a month and a half—as lovely as that sounded—I did want to give myself a few days off before looking for a job and an apartment so I could acclimatize to my new home and get over everything that’d happened since dinner with Paul. I needed to defrost from life in Melbourne.

The butterflies that had skipped about in my stomach while I sat on the plane were finally calming down. Now, sitting here with my cup of rather average coffee, all I could think about was the fact that I had made it. I’d actually made it; I was now officially far away from Paul, far away from work, and far away from everything in Australia. My doubts about how I’d readjust to traveling after such a long hiatus were abating. I was living in Paris. I was doing it.

This is it, I thought, breathing in the lovely Parisian air and admiring my new surroundings.

I decided to sit a while longer and order another coffee. I checked out what my French comrades were drinking and followed suit. I wanted to feel like a local as quickly as possible. The espresso I ordered came quickly and I thought, Ah, this is better. Still a little bitter, but better. Despite the quality of the coffee not being what I was used to in Melbourne, I was in love with the fact that my café arrived with a tiny, individually-wrapped, chocolate-coated almond. What a fabulous addition to a caffeine hit. Why didn’t every café around the world do this?

At noon, well-dressed business people started filling the tables, which were covered with red-and-white check tablecloths. They sat, laughing together, drinking carafes of rosé, scanning the roving blackboard and ordering steak frites and salads. I looked on quietly, surprised at how happy all these groups of colleagues and friends seemed to be as they lingered over lunch, drinking wine, then coffee; many having dessert. I thought back to how bleak Melbourne had been before I’d left, with the majority of my coworkers eating miserable-looking salads at their desks as rain pelted the office building. I felt a wave of gratitude for the joie de vivre that seemed abundant here.

After a while, I began to sense that the waiters wanted my table for the lunch trade, and although they’d never say so directly, their exasperated looks eventually clued me in. I got up to continue my promenade up Rue de Bretagne.

After having spent a couple of hours on a sunny terrace, it was lovely to walk under the shade of the tree-lined street, passing quaint little cafés, butchers, and bakers. My mouth watered at the smell of baking bread. By the time I walked past a chicken rotisserie and eyed the fat dripping onto a tray of very willing potatoes, I could barely contain my hunger. My stomach grumbled to life. Where to have lunch on my first day in Paris? I sang to myself in anticipation.

Chapter

7

I WAS LOOKING AT MENUS in restaurant windows when fate intervened and my eyes landed on a shop that stopped me in my tracks. The yellow sunshades drew me in like a homing beacon and my legs sped up in anticipation.

The “Fromagerie” sign above the store screamed out for me to pay it some attention, the word fromagerie a joyous blend of fromage and rêverie. I wondered if anyone else had ever noticed this before.

Oh yes, cheese is always the answer, I said to myself, and approached the window greedily, my surroundings blurring into insignificance as my eyes locked on the window display. It was cheese, real French cheese, in all its glory. The fromagerie—which was highly likely to become my new local—was one of those quintessential French stores that sells one product and does a damn fine job of it. The windows and cabinets were lined with dozens of cheeses, covering a huge array of shapes, colors, and textures. There was round cheese and long cheese, moldy cheese and gooey cheese. Some cheeses were thin and some were thick, and one of them had holes in it that would put cartoon drawings to shame. There were tiny cheeses covered in raisins, fluffy white cheeses in little wooden containers, and huge wheels bigger than my head. My mind flashed back to the deli section of my local supermarket in Australia and I laughed thinking about how exciting cheese shopping would be now that I lived in Paris.

I inhaled deeply, the smell of farm animals, mold, and other indescribable odors hitting me in a wild wave, even through the window. I stood staring for what felt like seconds but may have been hours, my mouth open in amazement. As I gazed farther into the shop, I spotted the salesman tending to his babies. He was tall with broad shoulders and looked different to how I pictured a French cheesemonger would (that is, as the spitting image of a young Gérard Depardieu). He was rugged, with a rough-cut beard and salt-and-pepper hair. His strong arms were visible under a striped blue-and-white top and his apron gave him an artisanal air. I instantly christened him Mr. Cheeseman.

He gave me a reserved smile.

I smiled back but hesitated before entering the store, tossing up whether to go in now, or wait until I’d learned a few more French words before embarking on my maiden voyage. I didn’t want to embarrass myself by pointing wildly at a cheese and then having Mr. Cheeseman rattle off a bunch of incomprehensible sentences to me. My nerves were getting the better of me and I nearly turned away, until I thought about the end product—cheese!—the food that had coerced me into coming to France in the first place; an indulgence I’d enjoyed since my first visit to Paris with Paul, before things had gone south. Thoughts of everything that had happened in Melbourne further fueled my desire to create a new cheese memory: one that wouldn’t be tainted by boyfriends or breakups.

Putting my fingers over the handle, I pushed the door.

And then I pushed, and pushed again.

Mr. Cheeseman looked at me sideways and tapped his watch. I kept trying to open the door until he came from around the back of the counter and turned a key on the other side.

“Nous sommes fermé entre midi et deux,” he said. I looked at him blankly and he followed up with, “Shut between midday and two.”

“Oh, pardon,” I said, flustered.

“Dix minutes,” he said, shutting the door abruptly.

Maybe not so friendly after all . . .

I went to get a bottle of water and then returned, my cheeks still tinged red with embarrassment. Don’t mess with a French person’s business hours, I told myself for future reference. This time, I successfully navigated through the door and was met with a neutral look that made me wonder whether my earlier faux pas had already been forgotten.

I immediately launched into my schoolgirl French. “Bonjour. Je voudrais . . . eh . . . a-chet-er fromage, s’il vous plaît, monsieur.” I stuttered that I wanted to buy cheese, grateful that my embarrassing attempts to converse only fell on the ears of the cheese and the man selling it. My efforts, however, turned out to be futile, as Mr. Cheeseman replied to me in perfect English without pause or hesitation.

“Well, mademoiselle, you have come to the right place.” His accent was glorious and thick, like the oozing wheel of Roquefort in the corner of the store.

“This is a beautiful cheese shop,” I replied in English, still stilted despite being a native speaker myself. I’d come over all flustered again.

“Merci,” he said, and then asked, “Are you American?”

“No, Australian.”

“That’s a long way to come to buy cheese. Are you visiting Paris?” He clearly wasn’t rushing to get me out of the store like he had been earlier. His two-hour lunch break must have been a good one.

“Yes . . . I mean, no. Err . . . I’m thinking of moving h

ere.”

“Moving here?” he asked with raised eyebrows. “But you don’t speak any French.”

Ouch!

“I’m learning,” I said, hurt by his all-too-accurate observation and promising myself I’d amp up my language efforts the next day.

“It’s a very complicated language. Hard for foreigners to learn,” he said, making me feel inept.

Mr. Cheeseman looked around thirty-five but had an air of a distinguished, older Frenchman about him that I found intimidating. If this was to become my local cheese shop, my efforts to start things off on the right foot weren’t going so well. I tried to think of something clever to say.

The seconds passed slowly.

I only realized I’d been standing immobile for quite some time when Mr. Cheeseman asked me if I wanted to buy anything.

I announced confidently that I’d like a small piece of Comté.

He answered me with a blank stare and I pointed at one of the giant cheese wheels in the cabinet to make sure he’d understood.

“Ah, Comté,” he said, a look of recognition crossing his face.

“Yes, Comté,” I said.

“No, it’s Comté, not Comté,” he told me, repeating the two pronunciations exactly the same way—at least, I couldn’t for the life of me differentiate between them. We moved on, thankfully.

“So what kind of Comté would you like?” he asked.

It hadn’t occurred to me that there was more than one kind.

Fromage a Trois

Fromage a Trois